Hyderabad: He was a man of enigmatic dualities. For the world, he put up an austere façade while concealing a convivial soul within. Outsiders saw him as a symbol of solemnity, a Nawab with a rare smile and an air of unapproachability. Yet, within the confines of familial bonds and friendships, a metamorphosis occurred. Nawab Mukarrum Jah Bahadur transformed into the affable man next door, reveling in laughter and sharing jokes.

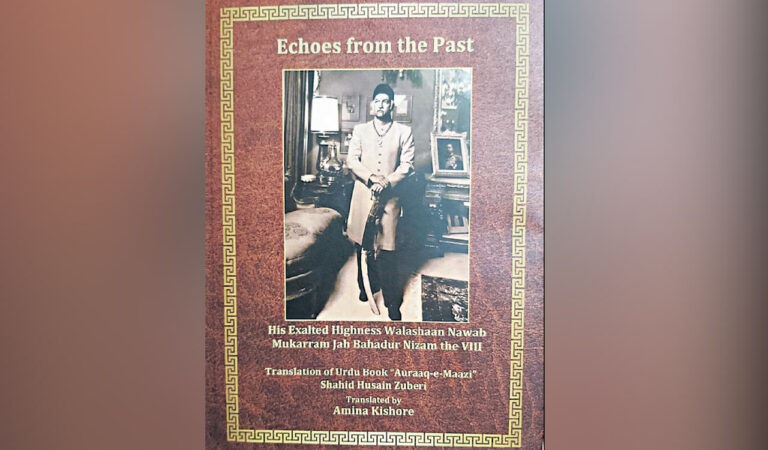

As the first death anniversary of Prince Mukarrum Jah Bahadur, grandson of the 7th Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan approaches, fresh details about his personality emerge. They unveil the vivacious and humorous soul beneath the regal veneer. A new book written by his confidant and close associate, Shahid Husain Zuberi, portrays the Prince as a sovereign of both power and wit. While being authoritative he reveled in the joy of camaraderie and jest. In his book, Echoes from the Past, Zuberi reveals a treasure trove of anecdotes which show that the Prince had a heart that beat. For the first time, a new dimension of Mukarrum Jah is exposed and little-known things of the eccentric prince come out.

The book was recently released at a function held at Salar Jung Museum by A K Khan, former Police Commissioner. Excerpts from the book read out saw the audience laughing from ear to ear. Zuberi, who served the titular Nizam for over two decades, earlier wrote the Urdu version of the book titled, Auraaq-e-Maazi. Its English translation is now done by Amina Kishore, a retired professor of English, Aligarh Muslim University and Maulana Azad National Urdu University.

Despite his professed loyalty to the 8th Nizam, Zuberi has been honest in bringing out the faults and foibles of Mukarrum Jah – warts and all. He tries to draw out the real Jah from behind the iron mask. Typically elusive, the Prince would become a paragon of respect and humility in the presence of elderly relatives. At a mehfil-e-sama (Sufi music session) he was seen carrying the footwear of his grand uncle, Nawab Basalat Jah. It so happened that the latter was trying in vain to draw his footwear near with the help of his walking stick. To the surprise of everyone, the Prince bent forward, and picked up the shoes, and kept them in front of Baslat Jah. “Mukarrum Jah’s respect for his close family members was phenomenal,” says Zuberi.

Mukarrum Jah’s persona leaves one perplexed as he was a victim of his circumstances. While he maintained a measured distance and a stiff upper lip in public, behind closed doors he was a man who embraced joy and laughter. There seemed nothing princely about him and his down-to-earth demeanor endeared all. He loved to crack jokes with his staff. Once he placed a card containing a funny quote on his opulent table. It read: Please don’t wake me up while I am working.

The Prince was fond of good quotes. He didn’t miss an opportunity to purchase cards with funny quotes or phrases. Once he found a card with the text: “I like my job. It is the work that I hate”. Mukarrum Jah bought three of them and placed them on the desks of his staff.

The prince had a penchant for blending laughter with his princely duties, delighting in the irony of his royal existence. If you have a yen for royal eccentricities and are interested in the real Mukarrum Jah, don’t miss reading this book.

4 months ago

4 months ago

English (US) ·

English (US) ·